What Happened in the Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad, fought from July 17/August 22, 1942 to February 2, 1943, was a defining moment in World War II. It took place in and around Stalingrad, now known as Volgograd, on the Volga River. This urban battle was the largest and most costly of the war. It pitted Germany and its allies against the Soviet Union, testing endurance on the Eastern Front.

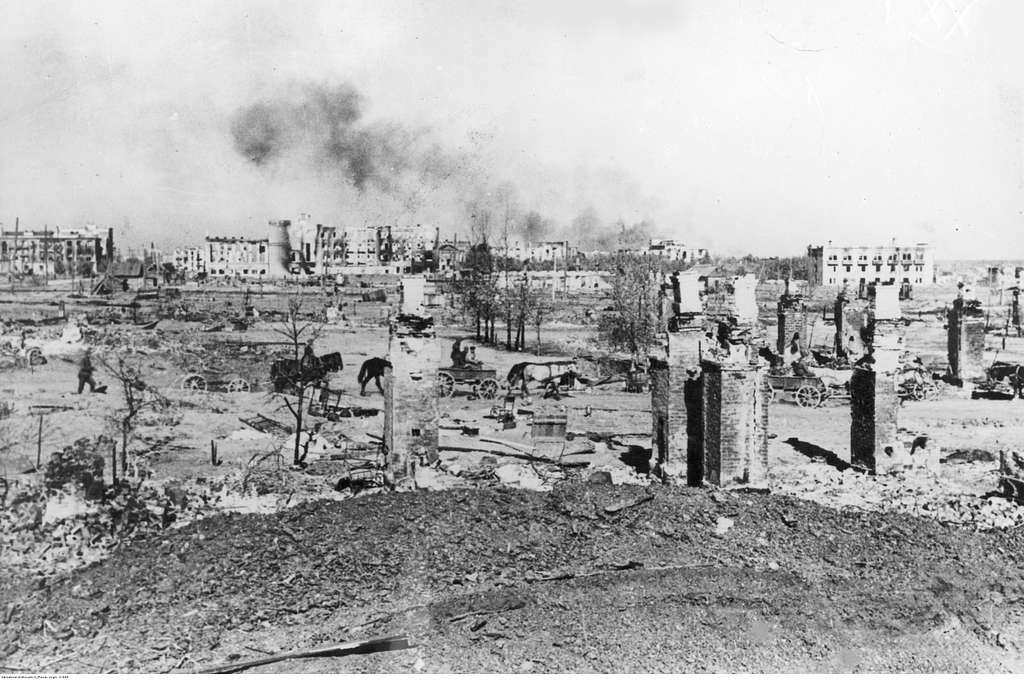

Stalingrad, stretching about 30 miles along the Volga, was home to vital factories. These factories produced armaments and tractors. After the German Army’s Case Blue campaign, the 6th Army and 4th Panzer Army moved towards the city. Luftflotte 4 provided air support. On August 23, Luftwaffe raids devastated the city, but the Soviet 62nd Army, led by Vasily Chuikov, held ground. They were backed by Order No. 227, a call to stand firm.

Operation Uranus, launched November 19–23, 1942, marked a turning point. Soviet forces encircled the 6th Army near Kalach. Adolf Hitler refused to allow a breakout, relying on an airlift that failed. Erich von Manstein’s Operation Winter Tempest was thwarted, while Operations Saturn and Ring further tightened the siege.

By January 31, 1943, Paulus surrendered. The last pockets of resistance fell by February 2. Axis forces lost over 800,000 men, with 91,000 taken prisoner. Only about 5,000–6,000 returned after captivity. Soviet losses were around 1,100,000, with 40,000 civilians also dying. The victory halted Germany’s advance and forced a retreat from the Caucasus, marking a significant turning point.

Stalingrad at the Crossroads: Strategic Importance on the Volga and the Eastern Front

The city of Stalingrad, situated on the Volga River, was a critical juncture. It controlled a vital supply route connecting the Urals, Caucasus, and Caspian to central Russia. This strategic location made Stalingrad a focal point for both armies, where the convergence of river, rail, and road dictated the battle’s trajectory. The siege of Stalingrad was as much a product of geography as it was of ideological fervor.

The control of the Volga River corridor was not just a military objective but also a logistical imperative. It ensured the flow of supplies from the Persian Corridor to the Red Army. German dominance here would have severely limited the availability of fuel, food, and ammunition. This understanding underscored the significance of the Volga line, as both sides anticipated a turning point in the battle.

Stalingrad’s Industrial Capacity and Transport Hub on the Volga River

Factories like the Dzerzhinsky Tractor Plant and the Barrikady and Red October works were instrumental in producing vital war materials. These facilities were connected to the Volga River by rail spurs, facilitating the transportation of troops and supplies. Despite the bombardment, production continued, with workshops relocating to basements and shop floors near the docks.

Even under intense fire, shallow-draft vessels played a critical role in transporting replacements across the river. This continuous flow ensured that Soviet forces remained operational, turning the siege into a logistical battle that neither side could afford to lose.

Symbolic Stakes of a City Bearing Stalin’s Name

The city’s name carried significant political weight, beyond its industrial output. Adolf Hitler aimed to capture Stalingrad as a victory that would resonate across Europe, symbolically defeating Joseph Stalin. Stalin, determined to hold the line, reinforced the city’s strategic importance with directives and personal visits by senior commanders.

Every inch of ground was a stage for propaganda, with reports from Berlin and Moscow amplifying the battle’s significance. This heightened the battle of Stalingrad’s turning point, influencing perceptions at home and on the front lines.

Case Blue, Operation Fischreiher, and the Caucasus Oil Objective

Führer Directive No. 41 outlined the 1942 objective: to seize southern resources. The operation, known as Case Blue, divided Army Group South into two parts. Army Group A aimed for Maykop and Grozny under Operation Edelweiss, while Army Group B targeted the Volga under Operation Fischreiher. The frequent redeployment of Hermann Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army stretched the German supply lines.

- Objective: cut the Volga and threaten the Persian Corridor route.

- Oil focus: deny the Caucasus fields to the Red Army.

- Command strain: frequent orders from Berlin delayed timelines and exposed flanks.

As the German forces reached the outskirts, the siege of Stalingrad began to take shape. The battle became a focal point where control of the Volga River was tied to the objective of securing the Caucasus oil fields.

Why Stalingrad Became the Battle of Attrition That Defined the Eastern Front

By mid-September 1942, Soviet forces held a nine-mile strip along the Volga River. Despite intense bombardment, ferries continued to transport vital supplies. Street fighting transformed buildings into kill zones, with control changing hands multiple times daily.

The Axis lines, held by Romanian, Italian, and Hungarian forces, were stretched thin. These gaps became critical vulnerabilities as the battle intensified. The relentless combat, coupled with logistical challenges, set the stage for a decisive shift in the war’s trajectory.

The battle of Stalingrad became a test of endurance, with time, shells, and blood being the currency of war. The siege was a testament to the strategic importance of Stalingrad, where every inch of ground was fought over with unyielding determination.

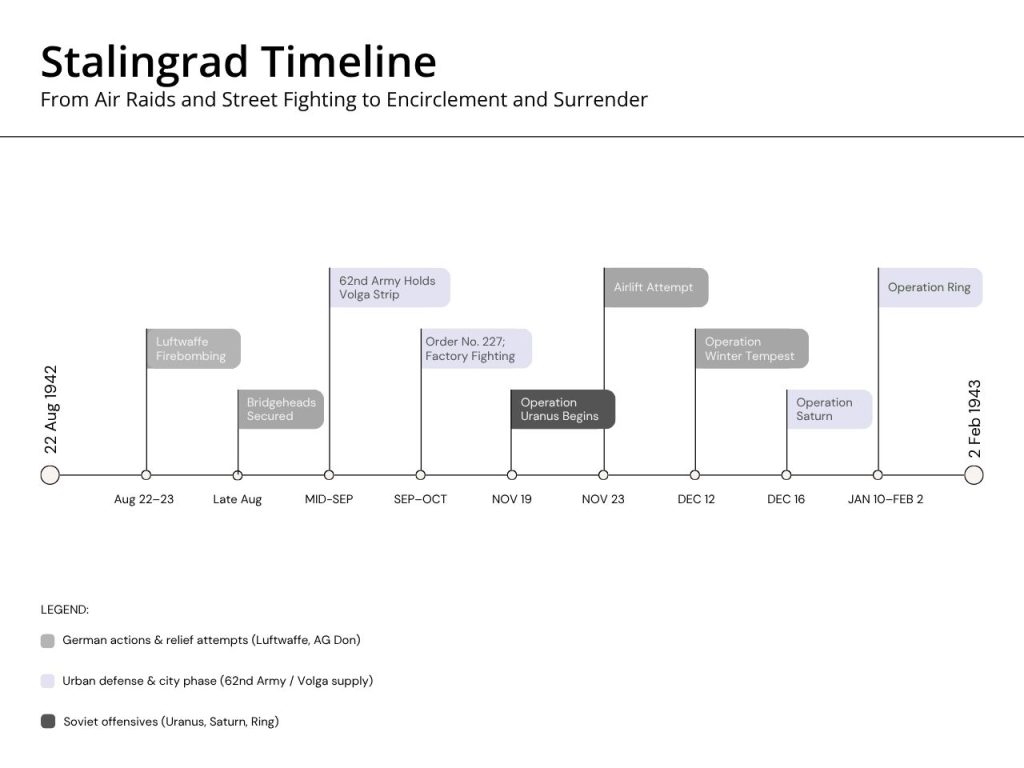

Stalingrad Battle Timeline: From Summer 1942 Offensive to February 1943 Surrender

The stalingrad battle timeline reveals a shift from swift advance to encirclement and attrition. It starts with Army Group B’s drive, narrows to intense city combat, and ends with supply collapse and formal surrender. Each phase illustrates how momentum shifted across the Volga steppe and into the city’s ruins.

Dates and Phases: July 17/August 22, 1942 – February 2, 1943

Initial clashes on July 17, 1942, erupted in the Don bend as the German 6th Army approached the city. The main assault began on August 22–23, after crossing the Don, allowing armored thrusts toward the Volga. By early September, fierce urban combat fixed both sides in a narrow corridor.

From November 19–23, 1942, operation uranus trapped the 6th Army and parts of the 4th Panzer Army. The pocket endured through December under air supply that never met its target. Capitulations on January 31 and February 2, 1943, marked the campaign’s end.

Key Milestones: Luftwaffe Bombardment, Street Fighting, Volga Crossings

- August 22–23: Massive Luftwaffe firebombing destroys large swaths of wooden housing and rail yards.

- Late August: Bridgeheads across the Don enable the 6th Army to reach Stalingrad’s outskirts by August 23.

- Mid-September: The Soviet 62nd Army holds a thin strip, two to three miles deep, along the Volga.

- October 14: German fire reaches the last crossing points; barges and boats ferry supplies under constant attack.

These milestones highlight the narrowing of the front and the extreme risk of Volga crossings. They show how the battle shifted from open maneuver to street-by-street fighting.

Turning Point: Operation Uranus and the Encirclement at Kalach

Georgy Zhukov, Aleksandr Vasilevsky, and Nikolay Voronov planned operation uranus, striking on November 19, 1942. Soviet pincers hit Romanian, Italian, and Hungarian units guarding the flanks north and south of the city. The linkup at Kalach, about 60 miles west, sealed the encirclement.

This ring trapped the 6th Army and isolated forward elements near the Volga. The move flipped initiative and set conditions for the german defeat in stalingrad, as relief grew unlikely and supplies dwindled.

Final Collapse: Operation Ring and the Capitulation of the 6th Army

Adolf Hitler rejected a breakout and relied on an airlift that delivered far less than required. Erich von Manstein’s Operation Winter Tempest advanced from the southwest in mid-December but stalled as Soviet forces pressed Operation Saturn.

On January 10, 1943, Operation Ring began to reduce the pocket block by block. Friedrich Paulus surrendered on January 31; remaining formations capitulated on February 2. The stalingrad battle timeline closes here, with operation uranus and the tightening siege culminating in the german defeat in stalingrad.

What Happened in the Battle of Stalingrad

The campaign on the Volga unfolded in distinct phases, revealing the essence of the battle of Stalingrad. It began with a swift summer advance, evolved into a brutal city fight, and ultimately turned into a trap that reshaped the Eastern Front.

German Advance Under Army Group B and the Push by the 6th Army and 4th Panzer Army

Army Group B, led by Maximilian von Weichs, moved east in 1942. Friedrich Paulus’s 6th Army and Hermann Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army spearheaded the advance. Hitler’s shift in focus towards the Caucasus introduced delays and strained supply lines.

Luftflotte 4 amassed around 1,600 aircraft by mid-September. On August 23, incendiary raids ignited Stalingrad, and German forces reached the northern suburbs. This marked the beginning of the intense street-by-street combat.

Soviet Defense Under Vasily Chuikov and Order No. 227: “Not One Step Back”

Joseph Stalin formed the Stalingrad Front with the 62nd, 63rd, and 64th Armies. Andrey Yeryomenko directed the sector, while Vasily Chuikov took command of the 62nd Army on September 11. Chuikov vowed to hold the line at all costs.

Order No. 227 prohibited unauthorized retreats and evacuation of civilians. This directive solidified the defense and narrowed the front to the Volga’s edge.

Urban Warfare and Close-Quarters Combat Along a Narrow Volga Bridgehead

The battle descended into close quarters combat. Trenches crisscrossed factories and courtyards. Assault groups advanced room by room, while Soviet forces launched constant counterattacks to prevent a German breakthrough.

By mid-September, defenders controlled a nine-mile strip, only two to three miles deep along the river. Supplies crossed the Volga under fire, keeping the bridgehead alive despite heavy losses.

Soviet Counteroffensive and Axis Encirclement Leading to German Defeat in Stalingrad

The strategic turn came with the Soviet counteroffensive, known as Operation Uranus. Instead of targeting the city’s core, Soviet forces attacked the overstretched Romanian, Italian, and Hungarian flanks north and south of Stalingrad.

The double envelopment closed near Kalach, trapping a quarter-million Axis troops. A stand-fast order, a failed airlift, and Erich von Manstein’s stalled Winter Tempest meant no breakout. Follow-on Operations Saturn and Ring tightened the noose, leading to the German defeat in Stalingrad and defining the battle’s outcome.

| Phase | Forces & leaders | Key actions | Operational effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Summer Drive (Jul–Aug 1942) | Army Group B; Sixth Army (Paulus); Fourth Panzer Army (Hoth) | Rapid advance; 23 Aug incendiary raids; entry into suburbs | Urban battle begins; logistics stretched |

| City Fighting (Sep–Oct 1942) | Stalingrad Front; 62nd Army (Chuikov); Luftflotte 4 | Order No. 227; factory fighting; Volga resupply under fire | Stalemate along a narrow bridgehead |

| Operation Uranus (Nov 1942) | Southwestern, Don, Stalingrad Fronts | Break Romanian/Italian/Hungarian flanks; close at Kalach | Sixth Army isolated |

| Relief & Collapse (Dec 1942–Feb 1943) | Army Group Don (Manstein); Sixth Army (Paulus) | Failed airlift; Winter Tempest; Saturn/Ring | Pocket split and surrendered |

Leaders, Armies, and Commands That Shaped the Siege of Stalingrad

The siege of Stalingrad was shaped by critical command decisions made under immense pressure. The control of the Volga River and rail lines significantly raised the strategic importance of Stalingrad for both sides. Every strategic move by field leaders played a decisive role in determining the city’s fate. The battle’s dynamics were influenced by air, armor, and infantry engagements amidst the ruins, highlighting the importance of leadership and logistics.

Axis Command: Friedrich Paulus, Hermann Hoth, Maximilian von Weichs, Erich von Manstein

Army Group B, led by Maximilian von Weichs, aimed to capture the Volga River to exploit Stalingrad’s strategic value. Inside the city, Friedrich Paulus’s 6th Army led the main assault. Hermann Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army was tasked with cutting Soviet crossings and expanding the breach.

Once encirclement was complete, Erich von Manstein formed Army Group Don to attempt a relief operation. Luftflotte 4 supported the siege with relentless air strikes. Commanders like Walter Heitz and Karl Strecker fought to hold shrinking sectors as supplies dwindled.

Soviet Command: Georgy Zhukov, Aleksandr Vasilevsky, Andrey Yeryomenko, Vasily Chuikov

Georgy Zhukov and Aleksandr Vasilevsky coordinated the counterattacks that reversed early setbacks. Artillery chief Nikolay Voronov orchestrated deep strikes, underscoring Stalingrad’s strategic importance beyond the city’s limits.

On the ground, Andrey Yeryomenko directed the Stalingrad Front, while Vasily Chuikov’s 62nd Army clung to the Volga Riverbank. Mikhail Shumilov and other commanders held key positions as reserves were built for the broader plan.

Allied Axis Flanks: Romanian, Italian, and Hungarian Forces on the Steppe

Romanian, Italian, and Hungarian armies stretched across the steppe front, with thin armor and limited anti-tank guns. These forces guarded vital supply routes, giving Stalingrad its strategic importance to the Axis campaign.

When Soviet armor concentrated on vulnerable sectors, these flanks collapsed under artillery and winter weather. Their failure widened the encirclement, altering command priorities across the siege.

Fronts and Armies Engaged: Stalingrad, Don, and Southwestern Fronts

The Soviet order of battle drew strength from three fronts that synchronized air and ground power. Their alignment tied city fighting to steppe maneuvers, reinforcing Stalingrad’s strategic importance at a theater scale.

Stalingrad Front held the urban line; Don Front contained Axis forces west of the city; Southwestern Front struck from the steppe. Together, they applied the pressure that shaped the siege of Stalingrad from riverbank to railway hub.

| Formation | Leaders | Core task | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Army Group B (Axis) | Maximilian von Weichs | Advance to Volga; take city sectors | Drove gains; exposed long flanks |

| Sixth Army (Axis) | Friedrich Paulus; Walter Heitz, Karl Strecker | Urban assault; hold bridgeheads | Became encircled focal point |

| Fourth Panzer Army (Axis) | Hermann Hoth | Cut Volga crossings; support urban push | Attrition and retasking slowed tempo |

| Army Group Don (Axis) | Erich von Manstein | Relief attempt (Winter Tempest) | Advance stalled; no breakout |

| Stalingrad Front (USSR) | Andrey Yeryomenko; Vasily Chuikov (62nd Army) | Hold city; fix German forces | Anchored Volga line |

| Don Front (USSR) | Konstantin Rokossovsky | Reduce pocket (Ring) | Surrender on 31 Jan–2 Feb |

| Southwestern Front (USSR) | Nikolai Vatutin; planning by Zhukov/Vasilevsky | Northern pincer in Uranus | Closed the encirclement |

Operation Uranus and the Soviet Counteroffensive at Stalingrad

Operation Uranus, launched on November 19, 1942, marked a significant shift in the Stalingrad battle timeline. It transitioned from static street battles to a mobile encirclement on the steppe. The plan aimed to strike the Axis flanks, avoiding the city center, and rupture the exposed areas. Within days, Soviet armor and cavalry moved swiftly toward key crossings, setting the stage for a major pocket.

Concept of Striking Weakened Axis Flanks North and South of the City

The Stavka targeted Romanian, Italian, and Hungarian units, placing them under immense pressure. These units were positioned north and south of the Volga bend, where defenses were weak and anti-tank support was lacking. Two shock groups advanced about 50 miles from the city limits, bypassing urban ruins to gain speed. This strategy aligned with the stalingrad battle timeline, shifting the focus from attrition to maneuver.

Encirclement at Kalach and Isolation of the German 6th Army

By November 23, the Soviet spearheads met at Kalach, sealing the crossings over the Don. This move trapped the German 6th Army and parts of the 4th Panzer Army. Estimates suggested around 250,000 troops were trapped, with fuel and food already in short supply. The Soviet counteroffensive at Stalingrad tightened its grip as artillery moved into range and forward airfields faced threats.

Airlift Failure and Operation Winter Tempest’s Stalled Relief Attempt

Adolf Hitler ordered Friedrich Paulus to hold his ground, relying on a Luftwaffe airlift that failed to meet daily needs. Bases like Tatsinskaya suffered heavy losses, and weather further hindered supply efforts. In December, Erich von Manstein’s Army Group Don launched Operation Winter Tempest, reaching close proximity. Yet, no breakout was authorized by Hitler.

Follow-On Offensives: Saturn and Ring Sealing Soviet Victory at Stalingrad

Operation Saturn began on December 16, expanding the attack against Axis rear areas and compressing the pocket further. With the Volga frozen, Soviet units hauled guns and ammunition across the ice, increasing pressure on the trapped forces. Operation Ring started on January 10, 1943, gradually reducing the pocket sector by sector. This effort aligned with the Stalingrad battle timeline, culminating in the German surrenders on January 31 and February 2.

| Phase | Dates | Primary Actors | Operational Aim | Outcome Snapshot |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Double Envelopment | Nov 19–23, 1942 | Red Army vs. Romanian 3rd & 4th Armies | Exploit weak flanks north and south of Stalingrad | Linkup at Kalach; 6th Army isolated |

| Airlift and Pocket Stabilization | Late Nov–Dec 1942 | Luftwaffe, 6th Army | Maintain 6th Army via air supply | Tonnage shortfall; airfield losses at Tatsinskaya |

| Operation Winter Tempest | Dec 12–24, 1942 | Army Group Don under Erich von Manstein | Relieve pocket from the southwest | Advance stalls; no breakout authorized by Hitler |

| Operation Saturn | From Dec 16, 1942 | Southwestern and Voronezh Fronts | Crack Axis rear and cut relief lines | Axis cohesion erodes; pocket tightens |

| Operation Ring | Jan 10–Feb 2, 1943 | Don Front under Konstantin Rokossovsky | Segment and reduce the encircled forces | Paulus surrenders Jan 31; final capitulation Feb 2 |

Casualties at Stalingrad and the Human Cost of Urban Warfare

Archives and postwar research reveal the immense loss at Stalingrad. The city’s ruins, a frozen steppe, and broken supply lines made every block a test of endurance. The casualties at Stalingrad are a stark reminder of attrition, influencing how historians view the German defeat.

Axis Losses: 800,000+ Casualties Across German and Allied Formations

Total Axis losses exceeded 800,000, with some estimates even higher. Germany’s 6th Army and 4th Panzer Army suffered greatly in street battles and on exposed steppe flanks. Later, Soviet recovery teams found roughly 250,000 German and Romanian bodies in and around the city.

- Italian casualties: about 114,000–130,000

- Romanian casualties: about 109,000–200,000

- Hungarian casualties: about 120,000–143,000

- Luftwaffe and armor: hundreds of aircraft and tanks destroyed or captured

These losses underscored the German defeat at Stalingrad, where attrition overcame maneuver.

Soviet Losses: Approximately 1,100,000 Military Casualties

Soviet forces lost about 1,100,000 during the campaign. Frontline divisions rotated through the ruins, often crossing the Volga by night. Winter, disease, and supply issues added to the toll, as much as German fire.

Civilian Toll and the Devastation From Luftwaffe Incendiary Raids

The August 23 Luftwaffe bombardment set fires that ravaged dense districts. Civilian deaths are estimated at roughly 40,000, many in the first days. Continued shelling and house-to-house fighting destroyed homes, clinics, and food stores, adding to the casualties at Stalingrad.

POWs and Survival: 91,000 Surrendered; Only 5,000–6,000 Returned

At the capitulation, about 91,000 Axis soldiers, including 22 generals, were taken prisoner. Most died in prison and labor camps over the next decade, with only 5,000–6,000 returning home. Their fate, shaped by hunger, cold, and disease, serves as a human coda to the German defeat at Stalingrad.

| Category | Estimated Losses | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Axis Military | 800,000+ total | Includes German, Romanian, Italian, Hungarian, and auxiliaries |

| German/Romanian Dead Recovered | ~250,000 | Recovered in and around urban zones post-battle |

| Italian Forces | 114,000–130,000 | Severe losses on the Don and steppe sectors |

| Romanian Forces | 109,000–200,000 | Flank units hit during Soviet breakthroughs |

| Hungarian Forces | 120,000–143,000 | High attrition in winter counteroffensives |

| Luftwaffe and Armor | Hundreds of assets | Aircraft and tanks destroyed or captured |

| Soviet Military | ~1,100,000 | Dead, wounded, missing, or captured across the campaign |

| Civilian Fatalities | ~40,000 | Primarily from August 23 incendiary raid and urban combat |

| POWs Captured | ~91,000 | Among them 22 generals of the encircled forces |

| POWs Who Returned | ~5,000–6,000 | Released over the following decade |

Why Stalingrad Was the Turning Point: From German Setback to Soviet Momentum

The outcome of the battle significantly altered the Eastern Front. The strategic importance of Stalingrad, situated on the Volga, is highlighted by many historians. This location, where industry and river routes converge, played a critical role. It’s why many consider the Battle of Stalingrad a turning point in World War II Europe.

End of German Summer 1942 Gains and Collapse of Army Group B at the Volga

Army Group B’s loss of its Volga bridgehead marked a significant defeat. The encirclement of the 6th Army and the 4th Panzer Army sealed their fate. This halt ended the German advance towards the Volga, halting their momentum for the season.

The setback compelled Berlin to reallocate reserves and aircraft from other fronts. This move weakened German strength across Europe, slowing their strategic pace.

Soviet Victory at Stalingrad and the Shift in Strategic Initiative

The Soviet victory at Stalingrad gave the Red Army the upper hand. By spring and summer 1943, Soviet forces advanced westward. They liberated key cities in Ukraine and crossed the Donbas.

Leaders like Georgy Zhukov and Aleksandr Vasilevsky exploited this momentum. They used deeper reserves and artillery to maintain pressure on retreating Axis forces.

Aftermath: Expulsion of Axis Forces From the Caucasus

With the Volga secured, the Axis forces retreated from the Caucasus. This move abandoned their goal to seize oil fields around Maykop and Grozny. The retreat relieved pressure on Baku and the Caspian routes, restoring Soviet control over vital energy corridors.

This shift highlighted the strategic importance of Stalingrad beyond its ruins.

Legacy and Memory: Hero City Status and The Motherland Calls Memorial

After the war, the Battle of Stalingrad’s significance was cemented in public memory. The Soviet Union declared Stalingrad a Hero City in 1945. The Motherland Calls statue and memorial complex on Mamayev Hill were unveiled in 1967.

These honors commemorate the fallen and the commanders buried there, including Vasily Chuikov. The site remains a focal point for commemorations in Russia and former Allied nations. It solidifies the Soviet victory at Stalingrad as a key chapter in the war’s history.

Conclusion

The Battle of Stalingrad, fought from the summer of 1942 to early February 1943, was a blend of strategy and hardship. Germany’s Army Group B reached the Volga, leveling districts with Luftwaffe raids, and pressed the city block by block. Soviet troops held a thin bridgehead on the riverbank, then struck back with Operation Uranus, sealing the encirclement at Kalach. This shift from assault to entrapment, and the grueling urban fight that followed, answers the question of what happened in the battle of Stalingrad.

When the airlift failed and Operation Winter Tempest stalled, the 6th Army lost any realistic exit. Operations Saturn and Ring followed, reducing the pocket and forcing surrender. The siege of Stalingrad cost more than 800,000 Axis casualties and about 1,100,000 Soviet military losses, with civilians shattered by firebombing and hunger. The data show a battle of attrition that drained manpower, armor, and morale on both sides.

The result reshaped the Eastern Front. It halted Germany’s southern drive, forced a retreat from the Caucasus oil approach, and moved the strategic initiative to the Red Army. For those measuring what happened in the battle of Stalingrad against the wider war, this was the hinge: from German momentum to Soviet advance, from city ruins to a broader reversal that would carry westward through 1944 and 1945.

Memory endures on Mamayev Hill, where The Motherland Calls rises over a rebuilt city granted Hero status. The siege of Stalingrad remains a stark lesson in industrial warfare, command risk, and the limits of supply. It also stands as a record of human endurance under fire, a turning point that defined the path to victory and the price paid to reach it.

FAQs

What Happened in the Battle of Stalingrad?

Germany and its allies fought the Soviet Union for control of Stalingrad. The Soviet counteroffensive, Operation Uranus, encircled the German 6th Army. This led to a failed airlift, a stalled relief effort, and Operation Ring, forcing the German surrender.

Why Was Stalingrad Strategically Important?

Stalingrad was a critical transport hub on the Volga River, housing vital armaments and tractor factories. Its control threatened Soviet supply lines and Lend-Lease via the Persian Corridor. The city also protected the Caucasus oil fields, making it a strategic stronghold.

What Made Operation Uranus the Turning Point at Stalingrad?

Soviet planners Georgy Zhukov, Aleksandr Vasilevsky, and Nikolay Voronov struck Romanian, Italian, and Hungarian-held flanks north and south of the city. The pincers linked at Kalach, trapping roughly a quarter-million Axis troops and shifting the initiative to the Red Army.

How Did Operation Ring Lead to Capitulation?

After the failed airlift and Manstein’s stalled relief, Soviet forces launched Operation Ring on January 10, 1943. Systematic assaults split the pocket into sectors. Friedrich Paulus surrendered on January 31; remaining pockets yielded by February 2, ending the siege of Stalingrad.

How Did Operations Saturn Secure Soviet Victory at Stalingrad?

Operation Saturn widened Soviet pressure against Axis rear areas, disrupting relief. Operation Ring began January 10, 1943, dividing the pocket, reducing strongpoints, and forcing surrender in stages, culminating on February 2.

Why Did the Luftwaffe Airlift and Operation Winter Tempest Fail?

The airlift from bases such as Tatsinskaya delivered far below daily needs amid aircraft losses and severe weather. Manstein’s relief thrust advanced from the southwest but lacked the strength and freedom for Paulus to break out, leaving the pocket to collapse.

What Were Axis Losses at Stalingrad?

Axis casualties exceeded 800,000 across German, Romanian, Italian, Hungarian, and auxiliary forces. The Soviets recovered around 250,000 bodies in and around the city. Losses in armor and aircraft were heavy, hollowing out Army Group B’s combat power.

What Were Soviet Military Losses During the Battle?

Soviet casualties reached approximately 1,100,000 killed, wounded, missing, or captured. The intensity of urban combat and winter operations drove losses higher than in many previous campaigns.

How Severe Was the Civilian Toll in Stalingrad?

Civilian deaths are estimated at about 40,000, many killed during the August 23 incendiary raids and subsequent street fighting. The bombardment devastated wooden housing and public services, compounding the humanitarian crisis.

What Happened to Prisoners of War Taken at Stalingrad?

About 91,000 Axis soldiers, including 22 generals, surrendered. Only 5,000–6,000 eventually returned home, with many dying in captivity due to disease, exposure, and postwar labor conditions.